A Short Survey of the Best Bach Recordings

Igor Toronyi-Lalic

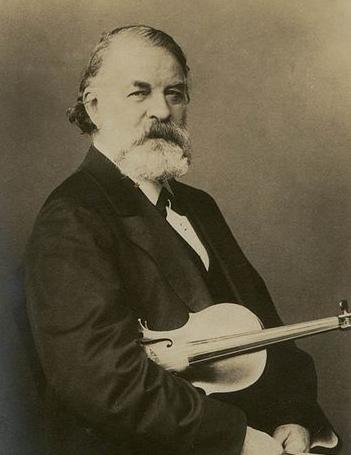

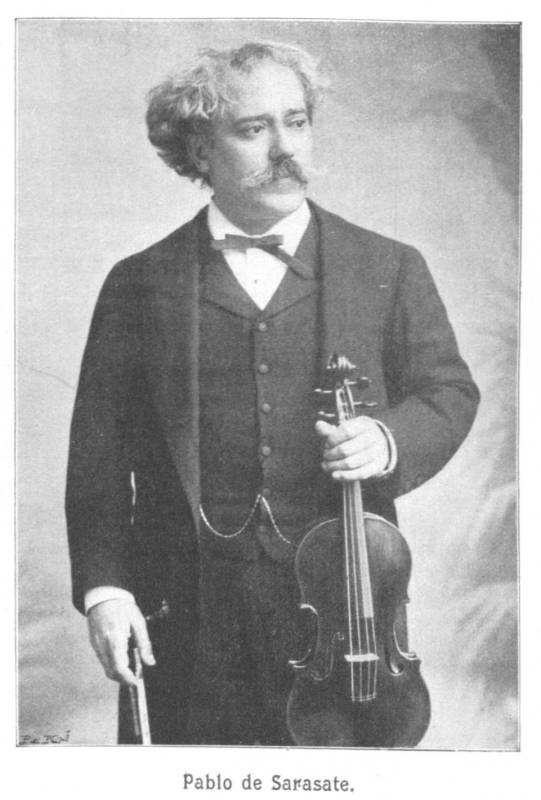

Let’s start with two zingers. The first ever recordings of Bach. You can find them on YouTube: Joseph Joachim, at the age of 72, in 1903, firing up the Tempo di Borea from the First Violin Partita. Chords crunch, notes spin, sparks fly. The second arrives a year later, Pablo de Sarasate joyriding through the opening Prelude of the Third Violin Partita, spitting out the bariolages at breakneck speed like a cocky sixth-former with a bet to win. It remains the fastest on record.

Not only do these performances remind you what a wild romp Bach can be, they also help dispel several canards: that old recordings mean stale recordings; that sluggishness and sentimentality reigned until the scholars came along; that a Whiggish curve of progress and enlightenment shapes 20th century Bach performance, in which the white knights of musicology rescue JS from the evils of romanticism.

What distinguishes a good Bach performance, then, is not style, speed, age, a sense of historical rightness. Quality cannot be determined by whether a recording is slow or fast, played with or without vibrato, on gut or metal strings, harpsichord or piano. The only question is: does the performance grab you by the throat or not? In the absence of agreement on a correct way to play Bach, the throat-grab test remains the only useful yardstick.

John Eliot Gardiner’s recordings will never not pin you to a wall. Listen to the way he turns the chromatic bassline in the duet of Cantata BWV 20 ‘O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort’ – which most other conductors allow to plod along without intent – into a phantasmagoric toothy menace that chases the singers and chomps through the aria like the theme tune to Jaws.

Of all the masterpieces in the Western canon Bach’s Cantatas – in essence, pocket operas – are probably the least performed and therefore most able to hit us with fresh force. Few other artistic hikes then are quite as rewarding as conquering Gardiner’s dramatic, cinematically vivid set with the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists. Some of the most unusual tableaux in all Bach flash up in BWV 20, 27, 80, 99 and 109.

The opposite problem applies to the solo instrumental works. As pinnacles of each instrument’s repertoire, and so frequently performed – even by those who maybe shouldn’t – it’s hard to squeeze anything new from them. Menhuin, Heifetz, Haendel, Podger, Grumiaux all dazzle scaling the mighty Chaconne. But check out Monica Huggett. Her capricious, conversational way humanises this Everest, turns it into something teasing, conspiratorial, gossipy, addictive. It’s the stray cat of Chaconnes, the sound straggly, the broken chords arching flirtatiously, Huggett running ahead of herself, then turning back to check who’s still with her.

In the cello suites a glossier sheen makes sense: the silky sound of Alisa Weilerstein or the dark purr of Daniil Shafran. Bathe in the ocean-black colours of Shafran’s C Minor Prelude (Doremi). Marvel at the long desolate sweep of the D Minor Suite. It’s Bach as a Tarkovsky tracking shot. For the faster dances you really want something that smells less of petrol and tar. Head for Casals’s pioneering, infectious thirties recordings, so sunny and springy in the G Major and E-flat Major gigues.

When it comes to the best recordings for solo piano, few would disagree on where to start: Dinu Lipatti’s First Partita, a pearly miracle (Warner). Beyond that I’m drawn to the weirder edges of this vast field. Sviatoslav Richter bouncing around dementedly in the C Minor French Suite Gigue, or scampering through the chromatics of the Fantasia in C minor (Stradivarius). I could live in the mysterious, atmospheric gothic spaces Angela Hewitt, Richard Tognetti and the Australian Chamber Orchestra delicately carve out in the Keyboard Concertos (Hyperion).

But what about the major sinners? What exactly does a bad recording of Bach sound like? In Willem Mengelberg’s infamous, epic 1939 St Matthew Passion the music is constantly sinking in on itself, collapsing in awe before the greatness of the notes. It’s Bach as cult. Obeisance in sound. Whether you’re a believer or not, Mengelberg doesn’t care. You are not worthy! What distinguishes a bad recording of Bach, then, is that you, the listener, might as well not exist.

Compare this devotional interpretation to the theatricality, intimacy and kinetic energy of Dunedin Consort’s St Matthew, each member of the tiny choir sounding like they’re inches from your ear. Conductor John Butt creates spaces you can enter, musical lines you can walk around, almost touch. It’s the Passion as VR. Or listen to Masaaki Suzuki’s ‘Herr, unser Herrscher’ in his exhilarating 2020 St John Passion, the choir on the attack, the oboes keening hungrily, the basses subwoofering like a BMW on the prowl.

Like Butt, Gardiner, Huggett, Hewitt, these are performances that want to bend your ear, draw you in, seduce, terrify. The listener is not taken for granted. Audiences must be won over. Just as they needed to be when Bach’s compositions were fresh. To be truly authentic then is to turn Bach into contemporary music again.

This is easier said than done for a work such as ‘Air on a G String’. How to remove the hardened deposits of sugar and starch built up over decades of valiant services to the Classical Chillout album? It remains one of the toughest asks. Perhaps you need to give in to the exaggerations? Wilhelm Furtwängler melts the orchestra into the work’s watery textures in his mesmerising 1947 recording with the Berlin Phil (Music and Arts) and lets it bloat to the size of a Mahlerian Adagio.

The benchmark for musical refurbishments is Café Zimmermann’s smoky Brandenburg Concertos (Alpha), full of sturm und drang vitality – tremors, thunder, trompes l’oreille – all marshalled to hallucinatory ends. Nigel Kennedy and Daniel Stabrawa have a similarly big, smouldering take on the Double Violin Concerto, with the Berlin Phil: sleety down-bows, oodles of sweet vibrato and wild runs dispatched with the swagger of a tennis pro acing every serve.

Older recordings can often feel newer than new ones, less self-conscious, more naive to the rules. Hear the effortless, shyly youthful 1946 rendition of ‘Sheep May Safely Graze’ BWV 208 by Elizabeth Schwarzkopf (EMI). Or seek out Harriet Cohen’s little known but beautifully subtle 1928 recording of selections of the Well-Tempered Klavier (APR). Or if you want to give a Bach purist a stroke play them Alfred Cortot’s electrifyingly wrong 1930s Brandenburg Concertos (EMI).

Bach’s daunting final exercises in contrapuntal mastery are the hardest to pull off, so wide are the expressive and textural demands – one second lamb-like, the next Boulezian. Richter and Hewitt again have the right combination of tenderness, touch and bite for the Well-Tempered Klavier, but Piotr Anderszewski’s furtive, feline 2021 recording of Book II seems set to become a classic. Konstantin Lifschitz’s magisterial Musical Offering, meanwhile, justifies Charles Rosen’s insistence that it be reclaimed for the keyboard.

What of the work of Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann? How could anyone resist the sadboi seductions of Tafelmusik’s recording of WF’s Adagio & Fugue, or the moreish melancholies of Christophe Rousset’s album of the harpsichord sonatas? CPE’s output is more robustly eccentric, moody and proto-Beethovenian. Listen to the stormy zigzagging of the OAE under Rebecca Miller in the B minor Symphony Wq182. Or try to remember that the piano sonatas on Mikhail Pletnev’s insane CPE album were all written before the 20th century. For pure bliss though, track down Arthur Balsam’s ravishing performance of CPE’s Concerto in D Minor Wq.23 (Bridge).

Beyond all this is a vast, joyous library of transcriptions. Those by Petri, Busoni and Kempff are essential. But, as an example of how an act of outrageous infidelity can lead to something truly loving, check out Blithe Bells (Hickox/BBC Philharmonic, Chandos), in which ‘Sheep May Safely Graze’ is given a fantastical Hollywood facelift by Percy Grainger.

Questions of authenticity haven’t detained us much. As early-music pioneer Niklaus Harnoncourt (author of a thrillingly unpredictable St Matthew Passion himself) has said, ‘an authentic, historically correct interpretation is impossible, an illusion or charlatanism.’ A truly authentic performance would need authentic 18th-century audiences. There is however one aspect of authenticity that should concern us. Seductive though these recordings are, they shouldn’t distract us from the real work of recreating these works in real spaces before real ears.

Watch Ton Koopman conducting the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir in ‘So ist mein Jesus nun gefangen’ from the St Matthew Passion on YouTube, to remind yourself how essential it is to be able to follow the physical choreography of singers (here the glorious duo, alto Bogna Bartosz and soprano Cornelia Samuelis), to see them entwine their voices, trace their bodies in the air.

To end, some footage of Bach himself. Or at least Gustav Leonhardt pretending to be Bach in Straub-Huillet’s film The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. Watch the opening, the great harpsichordist fizzing through the Brandenburg No 5 cadenza, zooming up and down the keyboard, the curls of his wig trembling, his body spasming.

There’s a similar fizzy fluidity to Bach’s handwriting. The notes are tadpoley, wriggly, sprung, ready to go. Visually his manuscripts beat, judder, jive, like Bridget Rileys. It’s all there. The primary job of any performer then is to leapfrog the past 250 years. Think back to before he became the Great JS, to when he was just another jobbing Bach, not even the most famous composer in his own family. Imagine him handing over those wet, smudged, fidgety scores. How to impress the anxious, eager maestro? How to win the audience? How to make the music sound new? It remains our greatest luck that the answers to these questions seem inexhaustible.

Igor Toronyi-Lalic, June 2022

Igor Toronyi-Lalic is the arts editor of The Spectator and director of the London Contemporary Music Festival. He is the author of the biography Benjamin Britten (Penguin, 2013) and What’s That Thing? (New Culture Forum, 2012), a report on public art.

This article was originally published in the production‘s programme.

Header image by Manuel Harlan.

The Bach Family

Stephen Roe

Sometimes an artist’s work is so transcendent that authorship by a single human being seems barely credible. Johann Sebastian Bach’s enormous output of over 200 church cantatas, passions, oratorios, organ and harpsichord works, orchestral and chamber…

More →

He Demands it All

Angela Hewitt

“Too weak in the treble and too stiff an action!” That’s something I’ve said about many a piano I’ve been expected to play during my more than fifty years on stage. It’s also what Johann Sebastian Bach evidently remarked when shown the first examples…

More →