The Necessary Biro

Harriet Lane

Earlier this year the Daily Telegraph ran a teaser in its print edition: ‘Jemima Khan: My verdict on the shake-up at Radio 2’. This was accompanied by a photo of Jemima Goldsmith, as she now prefers to be known. A forlorn tweet from the journalist Jemima Lewis followed: ‘My own newspaper appears to have mistaken me, their regular radio reviewer, for a millionaire celebrity. God, I miss subs .’

Not so long ago, journalism depended on sub-editors, those beady advocates for clarity and accuracy. Writers filed to editors; editors, once satisfied with the content and structure, handed copy over to subs; subs took care of the details. After checking copy for spelling, grammar, punctuation, syntax and compliance with house style, subs fitted the text into the layout and provided the ‘furniture’, the headlines, standfirsts, pullquotes and captions. But as technology demanded more content, and faster, many of those checks were dropped, and swaths (quibbles? Obstinacies?) of subs lost their jobs. The Telegraph, like many other media organisations, recently dispensed with most of its in-house subs: the bulk of its subbing has been outsourced to a Press Association hub in Yorkshire.

Digital media, with its emphasis on immediacy, clicks and cutting costs, has little time for the patient art of subbing, which is now considered frou-frou, a bit of an extravagance. A mysterious, half-seen world is vanishing and the evidence is there every time you pick up a newspaper or visit a news site.

Even in their glory days, sub-editors were underappreciated. Margaret Ashworth spent 39 years at the Daily Mail, ascending to the position of splash sub under the then-editor Paul Dacre, who ‘never really grasped what subs do, apart from, as he sees it, holding up production. I think he fears subs as people in the Middle Ages feared monks, because they were the only ones who could do the magic reading and writing.’

Subs were never much liked, because they knew too much. They saw it all: your infelicities, purple passages, mixed metaphors, your inability to distinguish between stationery and stationary. They knew where the bodies (and the ledes) were buried and because of this they were resented and sometimes thrown under the bus. Writers have always accused subs of missing the point, butchering the intro, cutting the best lines. It’s hard to love the people who kill your darlings.

There is a painful episode in Jonathan Coe’s 1994 novel What a Carve Up! when Michael, a burned-out writer, is commissioned to review a new book by his bête noire, a literary superstar. Having toiled carefully over his hatchet job, Michael is particularly pleased with the last word of his last line: ‘I suspect, finally, that he lacks the necessary brio.’

‘Not only was I sure that it put a perfect end to the review, but I also knew, as if by some telepathic process, that it described the single quality which he, in his most secret heart of hearts, would yearn to be credited with.’ Inevitably, when the review appears in the newspaper, a sub has transposed two letters so the review concludes with the line:

‘I suspect, finally, that he lacks the necessary biro.’

Last lines are often battlefields. Long after his restaurant columns are forgotten, Giles Coren will be remembered for his furious email to subs, an outburst which immediately went viral: ‘I am mightily pissed off… I don’t really like people tinkering with my copy for the sake of tinkering. I do not enjoy the suggestion that you have a better ear or eye for how I want my words to read than I do… It was the final sentence. Final sentences are very, very important… You have removed the unstressed “a” so that the stress that should have fallen on “nosh” is lost, and my piece ends on an unstressed syllable. I have written 350 restaurant reviews for The Times and i have never ended on an unstressed syllable. Fuck. fuck, fuck, fuck.’ The Times, it should be said, still retains a strong team of staff subs, people who will have saved Coren’s bacon on countless occasions.

Writers take these saves for granted, but no one will save the subs. Like goal keeper Jordan Pickford, they stand heroically alone, constantly scanning for the inaccurate use of ‘fulsome’. Because subbing is all about apprehension, efficiency is directly related to cortisol levels. The editor who gave me my first job as a junior sub-editor later said she hired me ‘because I could tell you were the sort of person who would lie awake at night worrying about everything’.

I was a sub (not a terribly good one) for three years, and pretty much every minute was filled with dread. There were so many things my colleagues and I feared letting through: factual errors, spelling mistakes, ‘legals’, inconsistencies, repetitions, dangling participles, apostrophe catastrophes, those grisly little mix-ups involving ‘less’ and ‘fewer’. Despite our best efforts, things sometimes went awry and then we suffered the consequences. Deputy editors were forever storming over to the subs’ desk, screaming: ‘You all deserve to be horsewhipped.’ Though this wasn’t great for morale (there was a lot of sobbing in the stairwell), we accepted the point, because we knew this stuff mattered.

It still does. The details are important. It’s hard to trust a news source when its stories are littered with typos. Mistakes indicate a lack of care, possibly even of scruple. If a newspaper can’t get the name of its radio critic right, why on earth would you bother with its jambalaya recipe, let alone its editorial on Brexit?

Harriet Lane, February 2019

Harriet Lane‘s debut Alys, Always was longlisted for the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award and shortlisted for the Writers’ Guild Best Fiction Book Award. Her second novel Her was selected for the Waterstones Book Club and shortlisted for the Encore Award for best second novel. She has worked as an editor and staff writer at Tatler and the Observer, and has also written for the Guardian, Vogue and the New York Times.

This article was originally published in the production‘s programme.

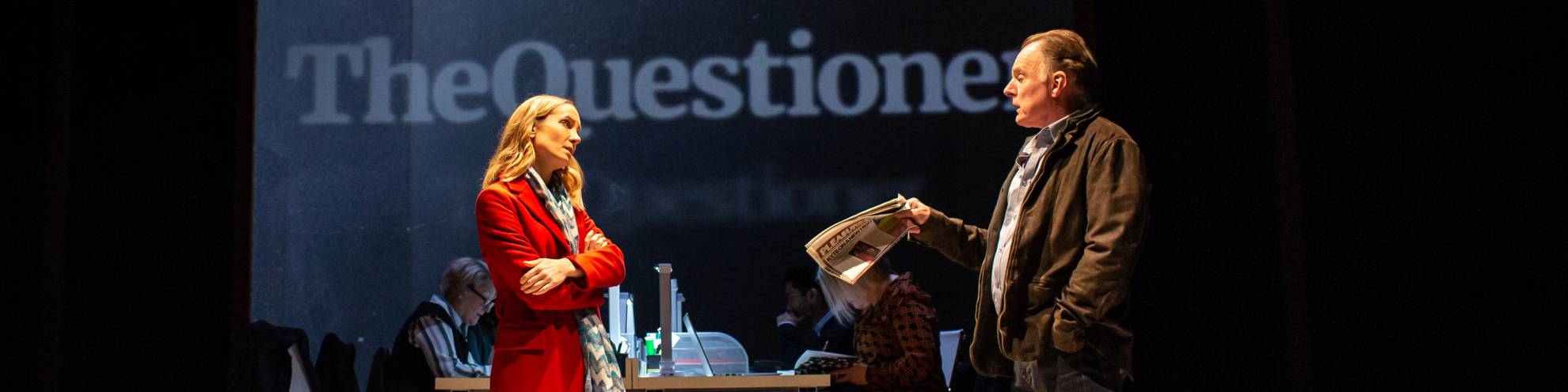

Photos by Helen Maybanks.

Further reading

The New Bright Young Things

Helen Lewis

Do you know the story of the first time Boris Johnson got sacked? It was in 1998, back before the affairs, before the lying about the affairs, even before the former foreign secretary made his name with stories about Europe’s war on bendy bananas…

More →