By the Virtue of the Dark

Marina Warner

During the long nights of the North before electricity, darkness gathered in the forests and below the blind black surface of the fjords; but beyond observable reality, another kind of night reached deep down in the depths, where monsters and phantasms lived and dangers and wicked pleasures threatened. Darkness was pitiless, it was diabolical, sin and destruction. In almost every culture hell is lightless and children need soothing to let themselves fall asleep and go down into the darkness where dreams rear up. In one of her weird, cantrip-like poems, the Scottish balladeer Helen Adam (d. 1993) asks:

Is it dark down there, Prince Horrendous?

Dark down there with Betsy Skull?

Is it dark down there

Where the grass grows through the hair?

Is it dark in the under-land of Null?

But the under-lands are also other worlds, secondary worlds of enchanted knowledge, and their inhabitants call out seductively, like Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci, or the weird goblin men with their succulent fruits in Christina Rossetti’s poem of initiation, Goblin Market. The Romantic poets were inspired by ballads and folk tales, and their fey cast of characters and binding spells, and they infused excitement into the fear of the dark: they were seeking it out on a quest for something more, finding the dark in themselves rather than out there in a supernatural cosmology of demons and fairies.

In his home town, Odense in Denmark, Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875) found ways into these secondary worlds; parents, grandparents, and neighbours passed on tales of trolls and mer-folk, goblins and demons – it was the last phase of a popular oral culture, before mass literacy. The material fermented in Andersen’s exceptionally fertile imagination, and he inflected the traditional fairy tale towards disturbance, morbidity, grim comedy, and shivery fatalism.

In Germany, older contemporaries, like the poet Goethe (1749–1832) and La Motte Fouqué (1777–1843), had created wonder tales, such as Undine, an inspiration for The Little Mermaid; in Austria, the bizarre imagination of E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776–1822) had produced the terrifying Sandman, who would come in the night to steal babies’ eyes to feed them to his own children; for Freud, the story epitomised the principle of the Uncanny. The minds of children became the Romantics’ ideal source of wild, pristine wisdom, untethered by reason or social norms, and fairy tales promised a pure connection to the ‘sense of something far more deeply interfused’, as Wordsworth put it. The Grimm Brothers, Andersen’s contemporaries, called their collection Children’s and Household Tales, but whereas the Grimms flinched at the savagery in the stories they were collecting and in several cases tried to soften their plain speaking and dark dealings, Andersen prided himself on honesty, and this meant facing the cruelty of reality. He wrought terrible, poignant fates for his Fir Tree, his Little Mermaid and the Little Match Girl. Punishment and loss, comeuppance and mutilation are his dominant themes – the splitting of the Little Mermaid’s tail, the cutting off of Karen’s feet in The Red Shoes. Although hope lifts some stories, such as The Ugly Duckling, most of Andersen’s fairy tales end in death. His masterpiece, The Snow Queen, arrives at a redemptive ending, but on the way we have been held, like Kai, in the icy grip of the Snow Queen’s love, and thrilled to the terrors she holds. In this extraordinary storyteller’s hands, fairy tales rarely open on to the light.

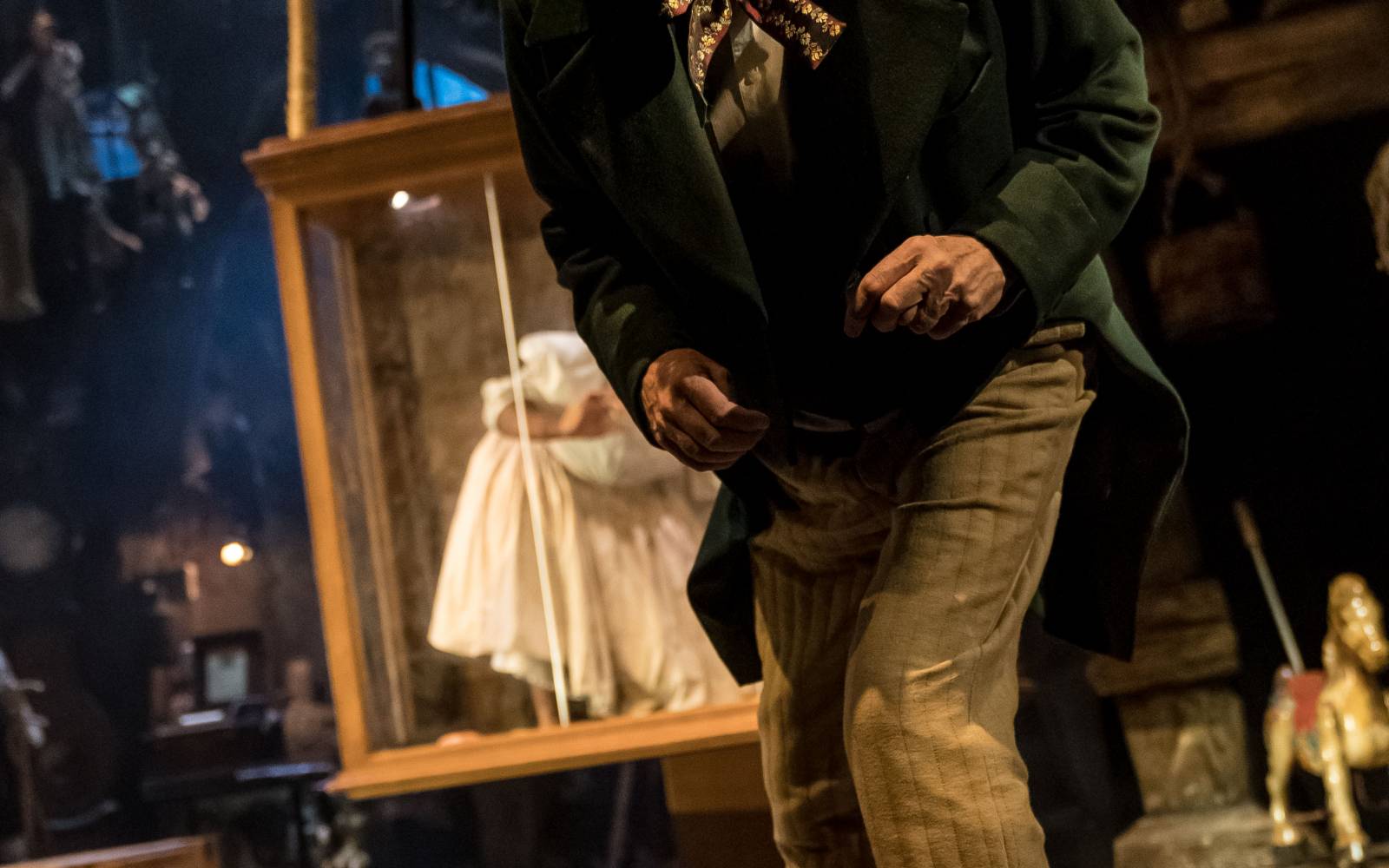

Dickens shares Andersen’s streak of morbid imagination, and much besides. Both writers have a humorous, gemütlich or cosy side, both were brilliant showmen and accomplished performers of their own work, who addressed themselves to a young audience but kept parents in earshot, introducing many touches to appeal to adult, worldly experience. Both were sincerely concerned with the misery of the poor, especially children: Jo the crossing sweeper in Bleak House is a brother to the Little Match Girl. Both writers mix light trifling wit and a jolly manner with cartoonish hyperbole and maudlin scenes involving children. Both can be very peculiar indeed. Andersen took the fairy-tale principle that everything in nature is animate and stretched it to encompass needles and stiff collars and tinder boxes and flying trunks: he was re-enchanting the banal everyday. Dickens likewise brings door-knockers and oil lamps to life in A Christmas Carol. This liveliness is creepy, especially as it is usually doomed – ‘creepy’ is the word Martin McDonagh often uses in the stage directions to A Very Very Very Dark Matter.

Andersen’s variation on Hoffmann’s The Sandman takes up this unsettling, witchy tone; one translator renders the title, The Sleep-Maker, and describes his entrance: ‘He quietly opens the door and with a syringe, which he always carries with him, he injects so much fine milk into their eyes that children cannot keep their eyes open … Then he comes up close behind them and breathes on the nape of their necks until the children’s heads begin to droop with the weight….’ This spectre is another alter ego of Andersen, for he brings stories: he opens an umbrella over good children ‘and their dreams then become the most beautiful fairy-tales.’ On the Sunday night, the little boy Hjalmar is lifted up to meet the Sleep-Maker’s brother: ‘They also call him Death! Look, doesn’t he look terrifying just like in the books where he is portrayed as a skeleton. This is not so. And what you see on his clothes is all silver embroidery. Isn’t it a beautiful Hussar’s uniform?’

The analyst Adam Phillips has pointed out that for children a bogey who looks like a man next door (an old soldier in the street) is far more terrifying than an outlandish monster.

With The Shadow, in which the hero’s shadow takes on a life of his own – with frightful consequences – Andersen turned once more to the uncanny theme of the Doppelgänger or Double. The folk roots of this tale lie in pacts with the devil: in Adalbert von Chamisso’s Peter Schlemiel (which Andersen knew), the protagonist sells his shadow to the devil and then finds himself captive to his master’s every whim. Andersen projected on to the Shadow his own tormented character, his craving for attention, his social gracelessness, his conflict over his sexuality and his inability to inspire love: this foreshadowing of Mr Hyde succeeds in altogether crushing – deleting – any vestiges of Jekyll in him. The story begins, ‘In the hot countries, the sun is certainly scorching! People turn as brown as mahogany. Why, in the hottest countries of all, they’re even burned black.’

A Very Very Very Dark Matter picks up on such instances of casual 19th-century racial prejudice, which coalesces a shadow double with a captured and tortured pygmy woman who has been brought to Europe in the same way that explorers and empire-builders collected human ‘specimens’. The infamous exhibition of Saara Baartman in London and then in Paris, is well known; she was dubbed ‘the Hottentot Venus’ and after her death in Paris in 1815, her brain, organs, and genitals were put on view in the Musée de l’Homme. At the Hunterian Museum in London, another, anonymous African woman, then designated a pygmy, was pregnant when she died and was bisected and preserved in formaldehyde – the artist Helen Chadwick (1953–l996), was working on a Cameo portrait of her to grant her the recognition she had never had, but died before she completed it. (There’s no reference to this item that I can find in the Hunterian today; sensitivities now rightly prevent showing such a trophy of the colonial pursuit of enlightenment.) Andersen was aware of such practices, and the European powers’ imperial ambitions in Africa provides the context for a satirical late story, The Wood Nymph, set in the World Fair of 1857, in which the fish exhibited in a tank comment on the crowds of humans who are being displayed, they assume, for their entertainment and opinions.

The seeds of this new drama were perhaps sown in a short story McDonagh wrote around 20 years ago, called Shakespeare’s Dwarf, in which he stages a similar struggle between inner darkness and the public outer self. In an earlier play, The Pillowman (1995, first performed 2003), McDonagh raised another dark double, which inspired the artist Paula Rego, no stranger to the dark of family bargains, secrets and lies, to make a lumpy three-dimensional puppet and pose it in disconcerting tableaux for a series of paintings. In the new play, Andersen’s alter Marjory also offers a grim, self-lacerating, blackly humorous self-portrait, for throughout his considerable oeuvre, McDonagh has lifted the skin on a flayed body of dark terrors, private and public.

The dark was once the natural medium of supernatural forces, and then became the characteristic mood of psychological twistedness, madness, gloom, and despair. But since the Second World War a sense of horror rages around our nature as human beings and it seems that the need to plumb the dark to the very depths is growing keener, as audiences want stories to reveal the truth, however frightening and abhorrent; such horrors feel the right match for what is going on and has gone on. The American poet William Carlos Williams, contemplating his baby son waking up, wonders about ‘the huge phantasmagoria’ that never rests in a child’s mind, how through the power of make-believe his son sees ‘giants lean over him with hungry jaws…’ The prose-poem ends, ‘That which is known has value only by the virtue of the dark. This cannot be otherwise. A thing known passes out of the mind into the muscles, the will is quit of it, save only when set into vibration by the forces of darkness opposed to it.’

This latest play, from a master of the dark macabre and the psychological uncanny, vibrates in resistance to violence, bigotry, greed, destruction, with the energy of creative imagination; defying what Andersen and Dickens met in the Marsh King’s realm, the Snow Queen’s wilderness, the poor house and the slums of the Victorian era, he sees himself as the earlier writers’ heir and revisits their work in a gruesome, angry comedy, facing down the forces of darkness and willing them to stop.

Marina Warner, October 2018

Marina Warner’s most recent book is Forms of Enchantment; she is Professor of English and Creative Writing at Birkbeck College, London.

This article was originally published in the production‘s programme.

Photos by Manuel Harlan.

Further reading

The Inbetweener

Fintan O'Toole

When he was 16, Martin McDonagh told his brother John a story based on an old folktale: A lonely little boy is on a bridge at dusk when a sinister man approaches. The man is driving a cart on the back of which are foul-smelling animal cages…

More →

The Unfree Free State: An Overview of the History of the Congo

Mpalive-Hangson Msiska

One gets a better a sense of the Congo when the territory is seen in terms of its historical formation. Arguably, one of the most determining events for modern Congo was the late 19th-century founding of the Congo Free State by Belgium’s King…

More →