‘It’s One of the Most Radical Plays I’ve Ever Written’

Bim Adewunmi speaks to Suzan-Lori Parks, writer of White Noise

The origins of White Noise came from Suzan-Lori Parks herself.

Her 2014 play, Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2 and 3), set in the 1860s during the American Civil War, is about an enslaved Black man, Hero, caught up in the mess of a very particular conflict. Parks was watching the play, not for the first time, when one moment struck, and compelled her, anew. In the scene, in Part 2, two Black men are talking, and one of them is wondering what the world will be like when he’s free. “Say I’m walking down the street,” he says, “and the authorities come up to me and they confront me. ‘Hey, who do you belong to? Whose property are you?’ Well, what will I say at that? Will I say, ‘I belong to myself?’”

“There’s this kind of questioning that he’s posing to his future free self,” says Parks. “And watching that portion of my play night after night, I got to thinking, oh, there’s a play in that moment right there. And the moment spiralled, I could feel it spiralling right up, off the stage, into my heart — solar plexus area – and going, oh, that’s, that’ll be the next play that I’m writing.” The play became White Noise, which Parks had written by 2016, and which premiered early 2019. It tells the story of four friends caught up in a different kind of conflict. Parks calls it “one of the most radical plays I’ve ever written, because it’s the furthest outside my comfort zone”.

For artist and chronic insomniac Leo – a kind of descendant of Father Comes Home…’s Hero – the question of whom he belongs to in America is still a nagging query. And in trying to find the answer, he puts forth a shocking proposal, no trial balloon needed: voluntary enslavement, in which he is owned by Ralph, his best (white) friend for 40 days and 40 nights. The request is witnessed by the other two people that make up their interracial foursome, friends Dawn and Misha, respectively the girlfriends of the two men. (Spot the playful nod to The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in the characters’ names.) “The pain and rage need to get worked out of my system,” Leo says in the first act. “I’ll take myself to the lowest place and know forever after that, if I can bear it, then I can bear anything. And my mind will be free.” Leo’s thinking of James Baldwin (who taught a young Parks creative writing in college) when he says this, half-quoting him to say, “Like the brother said ‘Nothing can be changed until it’s faced.’” (The full quotation from Baldwin serves as the play’s epigraph.)

I tell Parks that what Leo is asking for feels like an idea outside of sense, and she agrees – until she doesn’t. “It’s outside of the framework of, you know, what one might do on any given rational day. And [Leo] is past that, you know? He’s telling it like it is. He is angry and everybody else is standing around pretending that the world is okay but he has lost faith in the system.” The question in Parks’ earlier play becomes moot: in a system that places more value in property than in a Black person’s life, is this not the natural apogee of the real status quo? “He’s got to protect himself because nothing else seems to work. And if he were seen as somebody’s property, then he would be valued. And if he’s valued, then the cops would leave him alone, you know?”

A lot of what Leo experiences will make him familiar to audiences: a Black man living in a functionally racist system who has had an encounter with police that has left him bruised and broken. But in his singular action, all the specifics of his life up to that point are important to note. The dots of his existence, when added up, lead him to where he ends up. Leo’s proposition appears out of seemingly nowhere but its roots are in the backstory Parks has him deliver in the play’s very first scene. And, by the play’s end, one can track what use is made of Leo’s ‘story’.

“You could say Leo’s had trouble believing in the system from childhood. And on top of that is his chronic insomnia, which disorients the brain,” says Parks. “So he’s not just a young man who’s been brutalised by the police. It’s not just that. He has had a long history of a disconnect.”

Each of the play’s characters gets a ‘solo’ – a monologue where they shade in some of the detail that stereotype might have otherwise filled in. “Every time I wrote a line for each of the characters, a solo or a speech,” says Parks, “I felt completely – as much as I could, being who I am, a Black woman, American person – as if I were completely in their shoes. Not all these characters are like me and to hear them, to take them in, I had to totally leave my terra firma.”

“Each of these friends think they’ve got the ‘woke’ thing down, Parks says. “And we all know people like that. Maybe we are even like that ourselves. During the course of the play each character might say something that’s hard to stomach. I’m interested in where audiences have the capacity to tune in, and where they tune out.” Ralph, passed over at work for a person of colour; Dawn, Leo’s white social-justice lawyer girlfriend Misha, Ralph’s girlfriend, who is Black, who knows she’s performing Blackness in a way that sits heavy on her soul…. Parks knows — that we all have a part to play in this.

“Leo steps out of the narrative. I mean, that sounds very gentle. He catapults himself out of the narrative,” says Parks, laughing but serious. “I feel like the play is asking, what if a character who had been pushed to the limit decides to put himself in an extreme situation, and what if his extreme situation brought up a lot of stuff for everyone in his immediate vicinity?”

You sense Parks pushing the audience to really consider complicity, and how easily and comfortably even ‘nice’ folks fall into roles that make them feel powerful, or avenged, or just good. It’s mostly Leo and Ralph’s terrible journey, but the repercussions are felt by the whole group. There’s no escaping humanity.

Suzan-Lori Parks’ storytelling prowess is renowned. It’s evident in the length and breadth of her career: playwriting, of course, but screenwriting for both the big and small screen, essays, a novel, and writing songs for her band, Sula & The Noise, in which she plays guitar and harmonica. Her Pulitzer, for Topdog/Underdog, made her the first Black woman to win for Drama back in 2002, but it’s just one big fish in a net of big fish: the Whiting Award, Obies, the Gish Prize, the MacArthur Foundation ‘Genius’ grant, a Guggenheim fellowship, a Tony award… The list of her accomplishments is huge, and deserved. The New Yorker critic Hilton Als described in 2016 Parks’ writing style: “highly stylised and poetic, a dreamscape of the soul.”

The dreamiest parts of White Noise are not necessarily in dialogue, but rather at the core of what is most disturbing Leo’s spirit. Parks is a fan of katabasis. “You know, where the hero goes into the deep, dark underworld in order to find that beautiful thing that can help the community.” It’s there in another play of hers, The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World A.K.A. The Negro Book of the Dead. “Leo’s doing katabasis: the dive into that darkest or that most difficult place to retrieve the Quest object that he thinks has to be there. ‘Cause I done looked everywhere else, and that’s the only place I haven’t really looked as closely as I might.’”

She discovered, when the play was presented in New York, that while the play speaks specifically to a Black–White dynamic, it resonates for audiences across various cultures and groups. For Black audiences, Parks thinks the play reminds them that “we can experience our truths, and unburden ourselves and really deal with our shit in the presence of the other. And hopefully uncouple ourselves from that co-dependent enmeshment that some people call Western civilization.” Her smile is wicked here, but sincere.

“White folks, they might uncouple themselves as well. That way we all might see how racism and capitalism work hand in hand. We could recognise the harm we do. We could shatter the illusion of scarcity mentality as it intersects with the tenets of equality, AKA basic righteous behaviour. Remember the Olympics this summer? Those two athletes who shared the Gold? The practice of equality could be like that.”

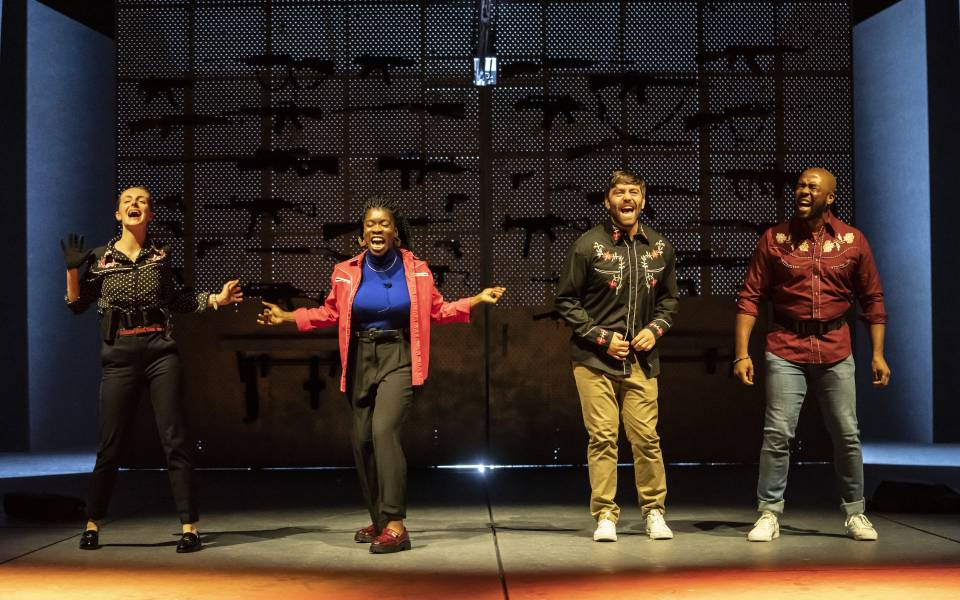

In the move to London, the action at The Spot has shifted from a bowling alley to a gun range, a change Parks really wanted to try. I float to Parks that both are deeply American symbols; cathedrals of American leisure. She nods. “Bowling is, I would say, an American church. Like a storefront church. Guns, shooting, that’s the American cathedral. And I really wanted to locate the play in an American cathedral that is so much a part of Ralph’s history.” And on the peculiarity of American racism, which I mention has many fathers, Parks is wry about White Noise landing in London. “Colonialism! Hey, England, nobody does it better!” she says, interrupting me gleefully. “So this play is like the prodigal child coming home. Saying, ‘hi, I’m home. Don’t you recognize me?’”

Bim Adewunmi, September 2021

Bim Adewunmi is a Nigerian–British journalist and playwright. She works as a producer at This American Life. Her play, Hoard, was staged at the Arcola Theatre in spring 2019. She lives in New York.

This article was originally published in the production‘s programme.

Header image by Muse Creative Communications.

All other photos by Johan Persson.

Further reading

To Be Black and Human is Not a Contradiction

Kojo Koram

The famous Martinican psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon once argued that “The Negro is not. Any more than the white man.” In making such a counter-intuitive declaration, Fanon was one of the first to publicly recognise that the racial…

More →

A Very American Story?

Olivette Otele

White Noise challenges our assumptions about the legacies of colonial enslavement. It explores the sources of anxiety in the characters’ relationships, as the spectre of enslavement plunges them into an experiment that will change their understanding…

More →