To Be Black and Human is Not a Contradiction

Kojo Koram

The famous Martinican psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon once argued that “The Negro is not. Any more than the white man.” In making such a counter-intuitive declaration, Fanon was one of the first to publicly recognise that the racial identities of being black or white, issues that were causing so much global turmoil when he was writing in the 1960s, did not actually exist in scientific or material terms. Racial identities were figments of our collective imagination that had been created by society, what today we fashionably refer to as ‘social constructs’.

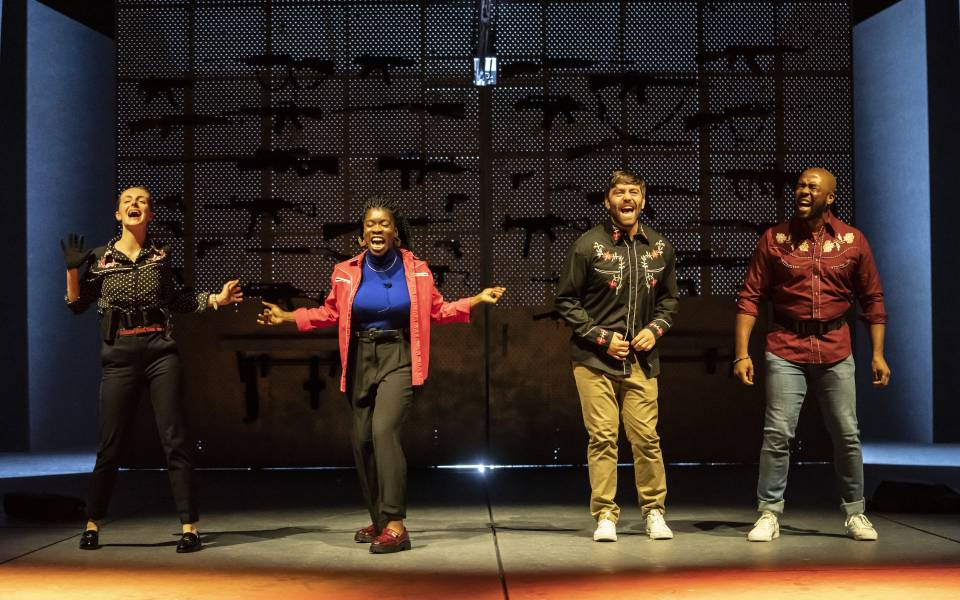

Yet just because race is not real, does not mean it does not matter. In the post-60s, post-civil rights era, we have been all taught to believe that race is real but it does not matter. In fact, it is the very opposite. And this fact rips through the cross-racial bonds that tie together Leo, Dawn, Misha and Ralph in Suzan-Lori Parks’ White Noise.

A friendship group predicated on an unspoken contract to minimise race has to face an event that violently inserts the topic back into their lives and highlights the extent to which each person’s sense of self is constructed in relationship to the racial identities of the others. There is a deep history that must be confronted, as the epitaph from James Baldwin that starts the play reminds us. There is an unresolved legacy of a not-too-distant past when half of the group could claim ownership over the other half, purely based on these invented identities.

So throughout this play the characters and audience must ask themselves: will confronting the legacy of slavery resolve the hurt and trauma that we continue to carry? What would confronting this legacy even look like? As a global society, we have been asking ourselves these questions in a more vocal manner ever since the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minnesota Police Force, which reverberated around the world in the summer of 2020. The video of that tragedy captured the dehumanisation of a Black American man that was so visceral, it couldn’t help but summon the ghosts of slaves from the plantations of the past. What had changed over the centuries? Did George Floyd show how some humans are still seen as equivalent to property existing only at the mercy of the bullet or the baton or the whip or the branding iron?

Statues of slave traders and plantation owners have started to be brought down in our major cities. The ways in which the transatlantic slave trade provided the foundations for many of our most famous institutions have started to be interrogated. Stately homes have started to speak about the bloody sources of their grand rooms. Football games have had to start to confront the racism that players have been facing for years, although the gesture of ‘taking the knee’ has prompted its own wave of anger. But the spectre of our racial past continues to haunt us.

The fallacy of race has been disproven by science multiple times but to no end. Biologically, the only reason the human species has managed to be so successful is because we have almost no genetic variation compared to other species. If we were dogs, we would all be the same breed – essentially just different colours of Labrador. This is why humans are able to reproduce, able to share vaccines etc. across racial lines.

So why does the fallacy persist? Is it because race is a fundamental sociological structure of human life? Is it because, without the enslavement and eventual death of the black person, this world could not exist?

This is the direction in which Leo’s quest takes him. This is “Afro-pessimism to the max”, as Misha tells him, making Leo the dramatic representation of a fashionable theory currently being promoted by scholars like Frank B. Wilderson III, who claims that “black social death” is the basis on which all other social relations occur. Even if the means of repression change and the plantation is replaced with the prison, the overseer replaced by the officer, the same structure of social life persists.

Perhaps this is part of the story. But unlike Leo, Parks remembers that there is also a material interest in continuing to believe in the fallacy. Race has made some people rich, and its afterlife continues to do so. Ralph’s position as a master is as tied to his new-found wealth as it is to his ideas about identity.

In Fanon’s writing, he took inspiration from the 19th-century German Philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, who analysed the “master–slave dialectic”’, explaining that both the slave and the master gain their identity through the interplay of recognition between each other. The master only knows he is the master because the slave recognises him as such and vice versa. There is a reward for the master for continuing to invest in this relationship.

But what of the slave? Can they continue to understand themselves through a dynamic that seeks to disqualify them from the category of humanity? The recognition that they receive from the master is a misrecognition, one that will inevitably provoke resistance, even if it is a long time coming. Fanon was not an Afro-pessimist and would not follow Leo’s quest towards the inevitability of black social death. He knew that eventually there must be a moment of assertion and believed in the inevitability and revolutionary potential of the black person one day crying out, ‘I too am Human,’ in defiance of a social system that was built, both in physical and ideological terms, on the presumption that the idea of the black human was a contradiction in terms.

Dr. Kojo Koram, September 2021

Dr. Kojo Koram is a writer and an academic, teaching at the School of Law at Birkbeck College, University of London. In addition to his academic writing, he has written for the New Statesman, The Guardian, Dissent, The Nation, and The Washington Post and has appeared on CNN and Sky News. He is the editor of The War on Drugs and the Global Colour Line (Pluto Press 2019).

This article was originally published in the production‘s programme.

Further reading

'It's One of the Most Radical Plays I've Ever Written'

Bim Adewunmi speaks to Suzan-Lori Parks, writer of White Noise

The origins of White Noise came from Suzan-Lori Parks herself. Her 2014 play, Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2 and 3), set in the 1860s during the American Civil War , is about an enslaved Black man, Hero, caught up in the mess of a very…

More →

A Very American Story?

Olivette Otele

White Noise challenges our assumptions about the legacies of colonial enslavement. It explores the sources of anxiety in the characters’ relationships, as the spectre of enslavement plunges them into an experiment that will change their understanding…

More →