Sounding Names

Peter Holland

In the summer of 2017 a number of Republicans in the US were incensed to learn that the New York Public Theatre’s production of Julius Caesar had Caesar made to look somewhat like (orange hair, red tie) and gesturing even more like Donald Trump. Few of those who vociferously complained that the production was recommending assassinating the President had noticed that Shakespeare’s play hardly makes a convincing case that murdering a political leader is good for the state that the conspirators support. In an even more remarkable demonstration of the pertinence of the play than the title character’s make-up in New York, Shakespeare companies all across the US began to receive hate mail, even though most recipients were not even performing the play. The name Shakespeare was apparently enough to warrant the ill wishes and, though none of the threats of rape and murder turned into violence, the fate of Cinna the poet of having the right name but being in the wrong place hovered disconcertingly over the vitriol.

As Orson Welles knew well in his 1937 production for the Mercury Theatre, precise analogies for Shakespeare plays are much less effective than broader ones. Subtitled ‘Death of a Dictator’, Welles’ Julius Caesar was full of fascist salutes, menacing black-shirted troops and echoes of Nuremberg rallies but his Caesar was neither Hitler nor Mussolini. Italian fascism and German Nazism were pointed towards but the argument of the production was not limited to them. Shakespeare’s argument about action in a threatened state speaks generally, not specifically.

In one respect, though, Shakespeare’s Caesar and Donald Trump share a striking trait: the tendency to speak of themselves in the third person so that ‘I’ becomes either ‘he’ or ‘Donald Trump/Caesar’. The technical term for this trope of what the Oxford English Dictionary calls ‘excessive use of the pronoun he’ is ‘illeism’. The effect is complex: sometimes it can seem narcissistic, a self-aggrandising definition of the public persona, a branding of the name as a kind of corporate logo with an identity apart from the individual: Trumpism as well as Trump, Caesarism as well as Caesar. But the separation of the self that is speaking from the self who acts can also be disconcerting, a sign of an anxiety about the kind of connection with – even a preference for a disconnection from – the speaker. Is the Caesar that Caesar speaks about the same Caesar as Caesar thinks of himself as being? There is, too, something performative in the language, a separation of actor from character, an indication of a theatricality and of a metatheatricality too, an awareness of being not oneself but a character – hence the use of illeism as a rehearsal technique for actors, a way of the actor presenting the character being played rather than representing it.

Caesar refers to himself as Caesar 19 times in the play, a remarkable frequency given that he is killed by the midpoint. By comparison, Hamlet speaks his own name 11 times in a much longer play and an enormous role – and seven of those are in a single speech, his apology to Laertes just before the duel: “Was’t Hamlet wronged Laertes? Never Hamlet”. Again and again Caesar says ‘Caesar’ as a sign of his authority and power. In itself this self-referencing seems an indicator of the would-be dictator that the conspirators fear to be imminent. Just before the conspirators begin their action, Caesar asks, “What is now amiss / That Caesar and his Senate must redress?”, not only speaking of himself but suggesting, with a quasi-royal arrogance, that the Senate belongs to him – “his Senate” – just as he responds to Artemidorus’ attempt to warn him with “What touches us ourself shall be last served”, using the first-person plural of the monarch. Caesar is a word that means much more than a name. In itself it had, by the time Shakespeare wrote Julius Caesar, come to mean an absolute monarch, a dictator, something Shakespeare had had Richard III mean when, offering to marry Queen Elizabeth’s daughter, he tells her she “shall be sole victoress, Caesar’s Caesar”. Quite probably pronounced then with a hard ‘C’, Caesar would have sounded closer to the German Kaiser than we now hear in the word. The Roman Emperors who would rule, starting with the play’s Octavius, would all be Caesars, a title, not a family name or Roman cognomen. The name points in Julius Caesar to its future meanings after the fall of the Republic, as if it already carries its status in later history, in a play strongly aware that it is itself a performance of an event, not simply the event itself: as Cassius puts it after the murder, “How many ages hence / Shall this our lofty scene be acted over, / In states unborn, and accents yet unknown?”, speaking English, not Latin, in a performance in a theatre in England, in a play that was by no means the first to deal with Caesar’s death. The first actor of Cassius – and everyone who has played the role since – are describing their own performances in speaking the lines.

But Caesar is not the only illeist (yes, that is the correct word for one given to illeism) in the play. Brutus says ‘Brutus’ ten times, the last being his announcement at the final battle that “Brutus’ tongue / Hath almost ended his life’s history”, that use of ‘history’ to mean something close to ‘biography’ that is Shakespeare’s usual sense of the word. If Caesar’s self-naming seems primarily narcissistic, self-centred, is the same necessarily true of Brutus’s? If Brutus is the paradigmatic portrait of the ineffectual liberal, confused in his reasoning, mired in impossible moral dilemmas over action and inaction, he also attempts to view himself, trying to stand outside his identity and looking at it. Illeism is, then, part of his analysis of that self he has that is trying to engage with and evaluate a commitment to political action.

Cassius, trying to persuade Brutus to join the conspiracy, weighs the two names against each other: “Brutus and Caesar: what should be in that ‘Caesar’? / Why should that name be sounded more than yours?” The answer to the question may be difficult but Caesar is certainly ‘sounded’ more than Brutus: in all, the word ‘Brutus’ is spoken 137 times in the full text of the play, the word ‘Caesar’ an extraordinary 202. That remarkable frequency is nearly three times the number of occasions ‘Hamlet’ is sounded in Hamlet. In the two scenes of Caesar’s murder and the funeral oration alone, ‘Caesar’ is spoken 89 times, including the moment when the two names Brutus and Caesar merge, as a member of the crowd listening to Brutus’ speech calls out “Let him be Caesar”. Antony, in turn, makes Caesar an archetype: “Here was a Caesar! When comes such another?” Caesar is a Caesar, not the Caesar, and another plebeian makes Caesar in death the king he was not in life: “O royal Caesar!”

But, beyond such names, Shakespeare fills his play with the names of others, many repeated far more often than is his practice elsewhere. The Senate is full of named people, far more of them than Shakespeare’s company could cast without doubling; modern productions, too, have to double but also often connect together different senators into one. When Publius (in this production Lepidus), one of the senators outside the circle of the conspirators, stands shocked and silent after the murder of Caesar (as Cassius describes him, “quite confounded with this mutiny”), Brutus and Cassius address him by name not once but three times in four lines: “Publius, good cheer”, “So tell them, Publius”, “And leave us, Publius”. When Brutus asks Voluminus (in this production Popilius), in the debacle of the battle, to help him die, he calls him over by name and then addresses him by it four times over, insisting that we hear and grasp this minor figure’s name. In Macbeth there are in the cast list thanes called Angus, Menteith and Caithness but their names are never spoken, simply used for stage directions and speech prefixes; for theatre audiences they are, in effect, nameless. But in Julius Caesar, Shakespeare is determined to have names heard and reiterated.

Except, of course, for one major group of characters. Not one member of the crowd, the mob, the plebeians, the workers, the commoners, the citizens or whatever else we or the play might call them, who fill the stage over and over again in the play – and who will also be the soldiers who died in their thousands at the battle Philippi – has a name. Of the two groups who make up SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus), the senators of Rome have names but not the people of Rome. Some, perhaps all, have trades, like the cobbler in the opening scene, when, according to the tribune Flavius, he “ought not walk / … without the sign / Of your profession”. Malleable, fickle and self-serving they may be, easily swayed by oratory and demagoguery, dangerous in the extreme, a many-headed monster. But they are also nameless, strikingly anonymous in a play so overstuffed with names.

Peter Holland, January 2018

Peter Holland is McMeel Family Professor in Shakespeare Studies in the Department of Film, Television and Theatre at the University of Notre Dame, USA.

This article was originally published in the production’s programme.

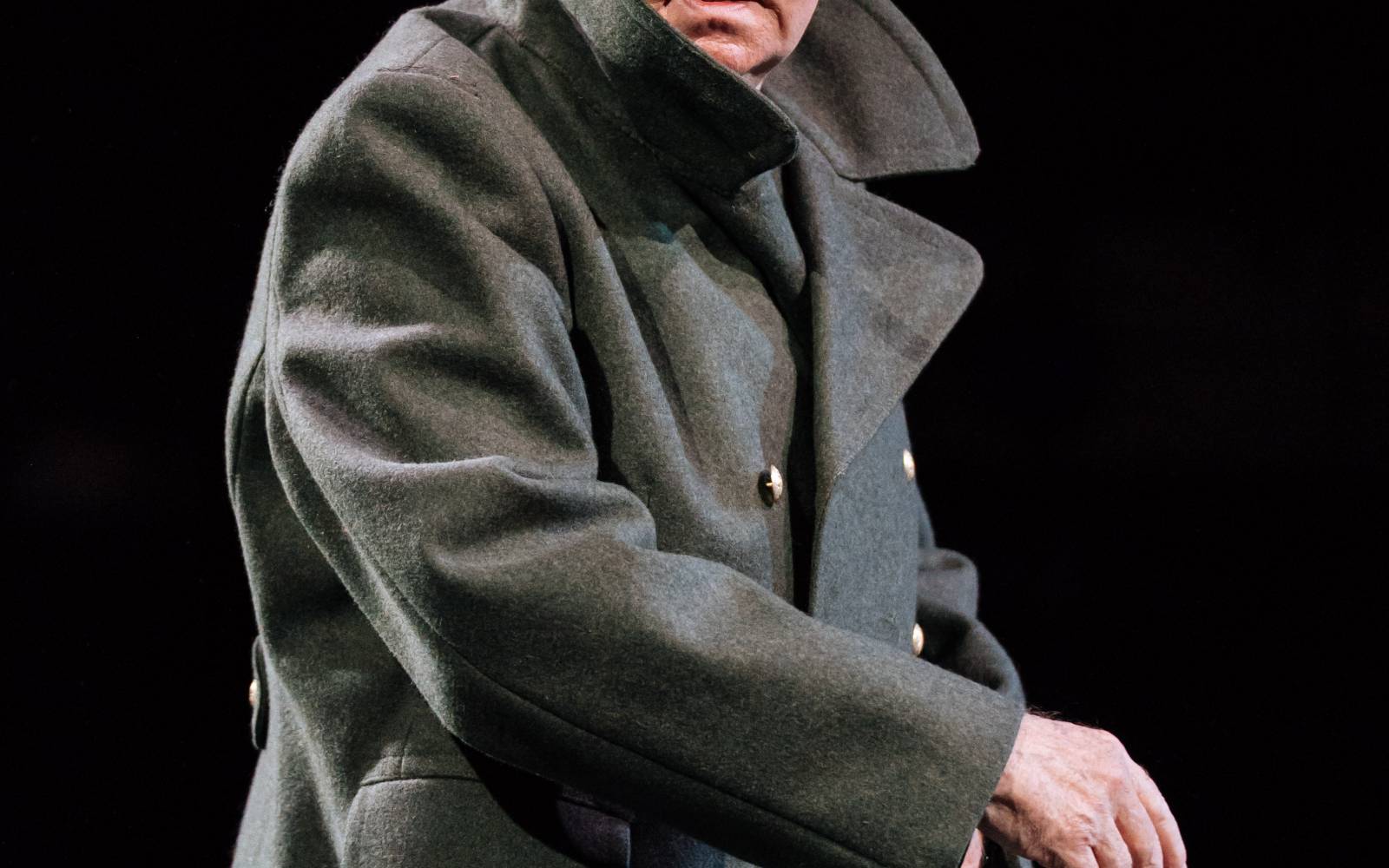

Photos by Manuel Harlan.

Further reading

The Assassination that Set the Template

Mary Beard

The murder of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BCE – the ‘Ides of March’ in the Roman calendar – is the world’s most famous assassination. It set the pattern for the future. For many of the Roman emperors who followed Caesar likewise came to violent ends…

More →

A Political Text for Our Times: Post Truth, Populism and Public Emotion in Julius Caesar

Matthew d'Ancona

“Cowards die many times before their deaths: / The valiant never taste of death but once”. On 16 December 1977, the imprisoned Nelson Mandela signed his name beside these lines from Julius Caesar in the hidden copy of Shakespeare’s works…

More →