The Bach Family

Stephen Roe

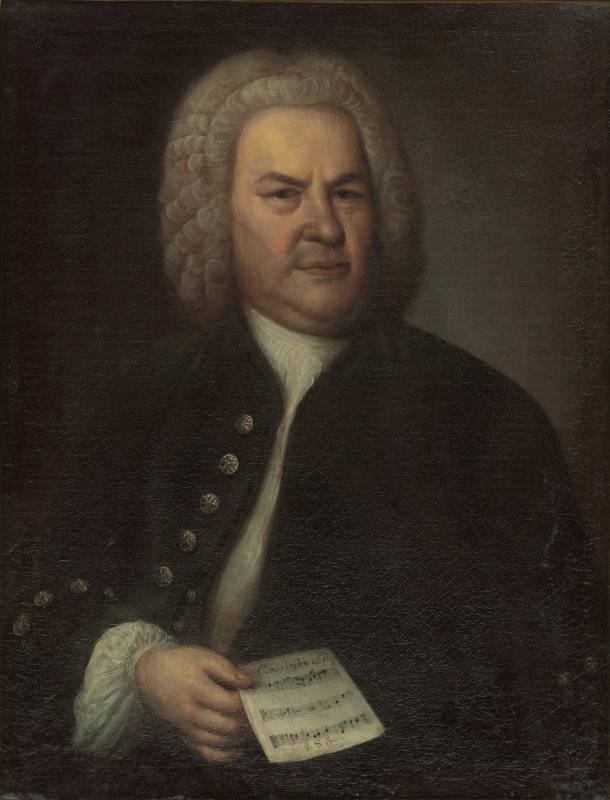

Sometimes an artist’s work is so transcendent that authorship by a single human being seems barely credible. Johann Sebastian Bach’s enormous output of over 200 church cantatas, passions, oratorios, organ and harpsichord works, orchestral and chamber music and concertos seems to contain only masterpieces, whether for the large forces of the St Matthew Passion, or the intimate beauty of his compositions for a single instrument – the violin, the cello, the lute. Almost all of these remained unpublished in Bach’s lifetime, rediscovered by Mendelssohn and others in the 19th century. Composing was only a part of his life. He was variously a choir trainer and director, organist, keyboard player, violinist, possibly even a singer, copyist, calligrapher, arranger and transcriber; he taught keyboard, music theory and composition. His pupils populated the churches and courts of Germany long after his death. His energy, verve and imagination seem super-human. Yet the only authentic portrait of Bach (opposite), by EG Hausmann, painted in Leipzig in 1746, four years before the composer’s death, depicts someone more down to earth: a well-built, formidable man. His piercing eyes (in reality clouded by cataracts) project authority and self-assurance. The only clue to his profession, a musical calling-card in his right hand, contains a complicated canon under the name ‘JS Bach’, a statement of his mastery of complex and arcane counterpoint.

Bach was not bashful about revealing his name in the portrait. He was inordinately proud to belong to a family network of composers, church musicians and town bandsmen, who had spread throughout southeast Germany after his ancestor, old Veit Bach, arrived in Thuringia in the 16th century, chased out of Catholic Hungary. Genealogy was an abiding interest for Bach, and he maintained a library of music of his forbears, which he performed and passed down to his own sons. It is through his eldest, Wilhelm Friedemann (1710–84), and especially Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714–88) that Bach’s music has survived to this day.

From Carl Philipp Emanuel’s short obituary of his father, we know that Johann Sebastian was orphaned when nearly 10 years old in his hometown of Eisenach, spending the rest of his childhood in his brother’s house in Ohrdruf. Though CPE Bach pretended that his father was self-taught as a musician, in fact he spent some years in Lüneburg during his teens, studying with Georg Böhm, and later making his celebrated walk from Thuringia to Lübeck to hear the great organist Buxtehude, whose music was an important early influence.

Bach’s first major appointment was at the Weimar court in 1708. He brought with him his wife, Maria Barbara Bach, a cousin, who bore the first six of his children there; a seventh was born in Köthen, where the family moved in 1717. In summer 1720, on returning from a visit to Karlsbad with his princely employer, Bach found Maria Barbara dead and buried, and he was left to care for his four surviving children alone. It is moot whether Maria Barbara ever knew the talented singer Anna Magdalena Wilcke, who became Bach’s second wife in 1722, assuming guardianship of the older children and becoming mother of 13 more. The family moved to Leipzig in 1723 where Bach had been appointed Thomaskantor, remaining there until his death in 1750.

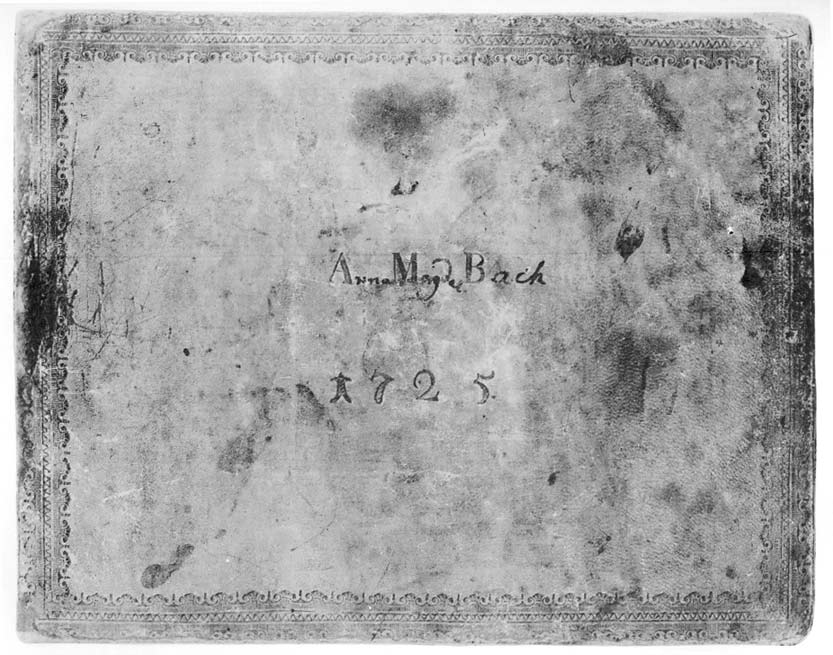

While music-making and religious education were the core of family life, Bach himself was known for his blunt outbursts and forceful statements of opinion. Family gatherings were enlivened by bawdy songs as well as hymns. Even Anna Magdalena transcribed a suggestive wedding song in the album known as Anna Magdalena’s Notebook (1725, pictured above). The music in this notebook and other works such as the Two and Three-Part Inventions and The Well- Tempered Clavier were the main educational tools for the Bach children, whose musical education was supervised by Bach and his spouses.

Wilhelm Friedemann (‘Willi’, in the play) was clearly an exceptional talent. Counterpoint exercises survive showing the young man’s first steps at composition, guided by Johann Sebastian. His dependency on his father somewhat limited his creativity and confidence. Johann Sebastian sought employment for him, but his career dwindled after his father’s death, leaving him in genteel poverty, seeking solace in alcohol. His fixation with his father took curious forms: one autograph composition of JS Bach survives with the author’s name deleted by Wilhelm Friedemann and replaced by his own. In another instance, he re-attributed one of his own compositions to his father. Carl Philipp Emanuel led a more stable existence. He found it easier to cut the paternal ties, showing a greater independence of mind and determination. He, too, established a large family and he and his half-brother Johann Christian became the most famous bearers of the family name during the second half of the 18th century, and an important influence on Mozart and Haydn.

It was to visit Carl Philipp Emanuel, who was working at the court of Frederick the Great, that Bach made his famous journey to Berlin in 1747, accompanied by Wilhelm Friedemann. Johann Sebastian was presented to the king, an amateur musician, composer, and quixotic flautist, resulting in The Musical Offering, a series of canons, fugues, and a trio sonata, all based on a theme composed by the king, who, though admiring of Bach’s effortless ingenuity, was unconvinced by his old-fashioned style.

This visit was the pinnacle of Bach’s professional life. Bach, constantly ambitious, endlessly sought public recognition for his art and battled indefatigably to uphold the highest musical standards. This zeal and stubbornness often caused resentment and on one occasion ended with a brief imprisonment in Weimar. A brawl with a recalcitrant bassoonist also allegedly landed him behind bars. Shortly after his return from Berlin, Bach realised the Leipzig authorities, aware of his failing eyesight and frailty, were preparing to replace him as Thomaskantor. Cornered, he fought this last battle to survive and won. Before he died in July 1750, aged 65, effectively blinded by the bungled surgery of the English oculist who later did for Handel’s eyesight in London, he could survey a life of stupendous achievement, a roster of students among the churches and courts of Germany and a large and talented family, with four great composers among his sons.

It was to visit Carl Philipp Emanuel, who was working at the court of Frederick the Great, that Bach made his famous journey to Berlin in 1747, accompanied by Wilhelm Friedemann. Johann Sebastian was presented to the king, an amateur musician, composer, and quixotic flautist, resulting in The Musical Offering, a series of canons, fugues, and a trio sonata, all based on a theme composed by the king, who, though admiring of Bach’s effortless ingenuity, was unconvinced by his old-fashioned style.

This visit was the pinnacle of Bach’s professional life. Bach, constantly ambitious, endlessly sought public recognition for his art and battled indefatigably to uphold the highest musical standards. This zeal and stubbornness often caused resentment and on one occasion ended with a brief imprisonment in Weimar. A brawl with a recalcitrant bassoonist also allegedly landed him behind bars. Shortly after his return from Berlin, Bach realised the Leipzig authorities, aware of his failing eyesight and frailty, were preparing to replace him as Thomaskantor. Cornered, he fought this last battle to survive and won. Before he died in July 1750, aged 65, effectively blinded by the bungled surgery of the English oculist who later did for Handel’s eyesight in London, he could survey a life of stupendous achievement, a roster of students among the churches and courts of Germany and a large and talented family, with four great composers among his sons.

Stephen Roe, June 2021

Stephen Roe is a music antiquarian and musicologist specialising in the Bach Family.

This article was originally published in the production‘s programme.

Header image by Manuel Harlan.

Further reading

He Demands it All

Angela Hewitt

“Too weak in the treble and too stiff an action!” That’s something I’ve said about many a piano I’ve been expected to play during my more than fifty years on stage. It’s also what Johann Sebastian Bach evidently remarked when shown the first examples…

More →

A Short Survey of the Best Bach Recordings

Igor Toronyi-Lalic

Let’s start with two zingers. The first ever recordings of Bach. You can find them on YouTube: Joseph Joachim, at the age of 72, in 1903, firing up the Tempo di Borea from the First Violin Partita. Chords crunch, notes spin, sparks fly. The second…

More →